The phase-out of coal for power generation is a political, rather than an economic decision, and has uncertain outcomes. To fulfil its obligations under the UNFCCC Paris Agreement of 2015, the European Union has decided to steadily wind down electricity production from solid fossil fuels – coal, lignite, peat and oil shale. For coal-intensive regions, this has led to or will lead to radical disruptions of coal value chains and labour markets. In response, the EU has agreed a Just Transition Mechanism mobilising around €55 billion over the period 2021-2027 to alleviate the impacts of the energy transition. Other, similar programmes also exist at the nation state level.

Coal industry’s position on just transition

The European coal industry supports the principle of a “just transition” and policies to implement it that are effective, fair and transparent. For example, EURACOAL members participate in the EU initiative for the coal regions in transition or “coal platform”, as well as the related initiative for the Western Balkans and Ukraine. These initiatives now sit under the broader Just Transition Platform that addresses the issues of a clean transition for all energy-intensive industries. The exchange of best practices and targeted support for those regions and companies undergoing transition are important aspects of the EU initiatives. An ideal just transition would enable coal companies to transform their businesses so that jobs are preserved. A productive dialogue between politicians, industrialists, trade unionists, citizens and other stakeholders can help to achieve this outcome.

Energy transition is a socio-economic challenge

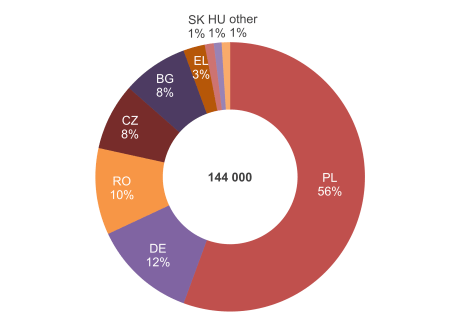

Three quarters of all coal-related jobs are in the mining sector. The regions with the highest number of jobs at coal mines and coal power plants lie in Poland, Germany, Romania, Czechia and Bulgaria. Even with a successful transition, it will be challenging to replace the long coal-value chains that support thousands of skilled jobs at equipment and material suppliers and service providers, as well as professional jobs for managers, engineers and scientists. The European Commission estimates that there are nearly 130 000 indirect jobs in coal-related activities (JRC, 2021). The regions with the highest shares of indirect jobs are found in Germany (Brandenburg, 28 000 indirect jobs), Poland (Silesia, 14 000 and Łódzkie, 7 300) and Romania (South-West Oltenia, 6 400). Other sources estimate that the coal-value chain – including power generation, equipment supply, services, research and development and other activities – supports 215 000 indirect jobs in the European Union (European Parliament, 2019).

Figure 7 – Share by member state of the EU total number of jobs at coal mines and coal-fired power plants, 2022 (Source: Table 1 above)

A big challenge is to mitigate the impacts of losing three hundred thousand direct and indirect jobs in a timely fashion. While early retirement can be attractive to some, younger employees in regions with coal phase-out plans face the risk of unemployment. Policy must encourage enough new jobs – ideally within the existing energy companies – to give continuity and stability during what should be a just or fair transition.

The Just Transition Mechanism offers compensation and vision

With its budget of €55 billion over six years, the Just Transition Mechanism aims to disburse around €9 billion each year between 2021 and 2027. For comparison, the turnover of the EU coal mining industry was an estimated €27 billion in 2022, while the value of coal imports into the EU added €21 billion to give a coal sector value of €48 billion. The value of downstream activities in power generation, so excluding coke, iron, steel and cement production, was approximately €110 billion. This hints at the scale of the challenge ahead: EU funds compensate for only a small fraction of the added value created each year by such a large industry. While jobs in one industry are phased out, new jobs need to be created. This requires public and private investment – tens of billions of euros – and a willingness by skilled workers in the coal industry to take up new positions in what are likely to be very different working environments.

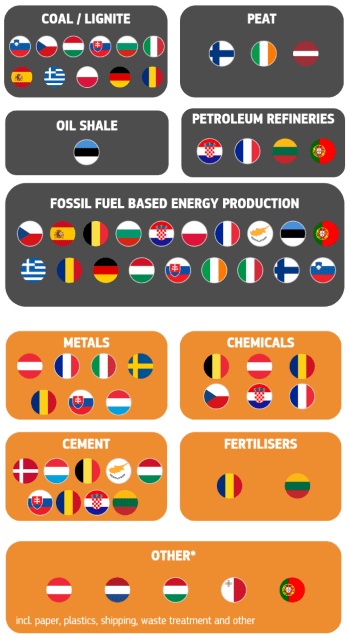

Figure 8 – Declining sectors (grey) / Transforming sectors (orange)

(Source: European Commission, 2021a, p.4)

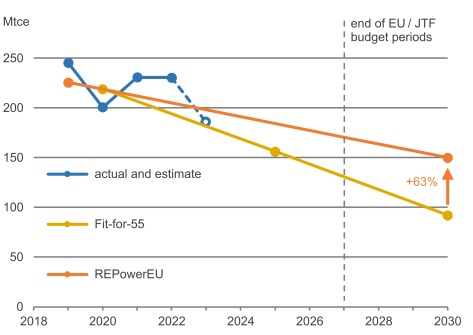

In 1997, Germany decided to phase down hard coal mining. In another key decision, taken in 2007, the policy switched to a phase out and the last mine closed in December 2018. Hard coal mining in the Ruhrgebiet and Saarland from 1958 to 2019 received public subventions of €152 billion (perhaps €500 billion in today’s money).1 For a just or fair transition, comparable sums and comparable timeframes are needed in other coal regions. In its REPowerEU initiative, the European Commission (2022b, p.10) aims at 36% less coal use in the EU by 2030 which would mean a 25% reduction by 2027 when the Just Transition Mechanism ends (Figure 9). So, the European Commission’s own projections show that the Just Transition Mechanism’s €55 billion covers only one quarter of the likely aid needed to transform the EU coal sector.

The costs of transition are not shared uniformly: the largest burdens fall on national governments, the coal regions, energy companies, and the citizens affected. EU funds are a small but politically important part of the whole as they can incentivise action. In Europe, the countries and regions facing the biggest coal phase-out challenges also have a lower per-capita GDP than the EU average (EURACOAL, 2020, p.12). This has been a factor behind the slower deployment of renewable energy sources in carbon-intensive regions. For example, the €81 billion of state support for renewable power generation in 2021 – over €180 per person (or €410 per household) – was skewed towards richer member states. While today, some renewable projects are auctioned, and costs have decreased, countries with tighter budget constraints have not developed as much clean power generation as their more affluent neighbours. Coal phase-outs are thus a matter of European cohesion, a policy area where the European Commission Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy can and does exercise its wide competences.

The citizens of Europe’s coal regions are the first to face the consequences of transition through rising energy prices, collapsing regional value chains and job losses. The EU ETS – now expanding to cover households and transport – is designed to increase the costs of fossil fuels for all consumers and so encourage energy savings and a switch to alternatives. However, paying for alternatives such as heat pumps is not always easy for consumers, so lower costs and targeted support are prerequisites for success.

Figure 9 – EU coal demand according to the REPowerEU Action Plan (Sources: European Commission, 2022b, Figure 1; Eurostat nrg_bal_s database, last updated 19.12.2023; and Eurostat nrg_cb_sffm database last updated 21.12.2023 (2023 estimate))

The Just Transition Fund in focus

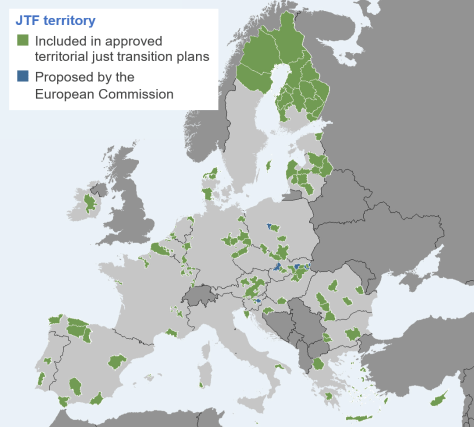

Since July 2021, the three pillars of the Just Transition Mechanism – the Just Transition Fund, the InvestEU “Just Transition” scheme and the European Investment Bank’s public sector loan facility – have helped reduce the burdens of energy transition in the EU coal regions. Eligible regions have a heavy economic dependence on the fossil fuel industry or other energy-intensive industries (e.g. steel, cement and chemicals) – territories were identified by member states and the European Commission. EU funds are allocated to the identified regions based on their territorial just transition plans which must be prepared to align with EU emission reduction targets for 2030 and on track to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

Figure 10 – JTF territories in the EU (Source: Just Transition Platform, DG REGIO, January 2024)

As of October 2023, most territorial just transition plans had been approved and the focus has switched to their speedy implementation to disburse funds during the EU multi-annual financial framework that ends in 2027. Funding aims to diversify local economies and “reskill or upskill” workers and jobseekers, alongside technical assistance and support for research and innovation, energy efficiency, renewables, smart and sustainable local mobility, digitalisation, soil regeneration, a circular economy, facilities for child- and elderly-care, and training centres.

Unfortunately, large enterprises can only benefit from funding for productive investments under very specific criteria, hampering the continuity of employment at long-established, regional companies who wish now to diversify their activities. Explicitly excluded is investment related to the production, processing, transport, distribution, storage or combustion of fossil fuels. This then would exclude environmentally friendly investments into, for example, efficiency improvements at district heating plants or the capture and use of coal mine methane at mines.

Projects selected in territorial just transition plans include the €19 million construction of a rare-earth magnet factory in Narva, Estonia, creating up to one thousand new jobs in an oil shale mining region, and decarbonisation projects at industrial processes in Sweden, such as the direct reduction of iron ore with hydrogen at a steel plant in Norrbotten to eliminate the need for coking coal, and the construction of a carbon capture and storage (CCS) facility at a cement works in Gotland. All these and others will keep industrial activity in the respective regions, saving jobs and value chains.

Figure 11 – Just Transition Fund (JTF) allocations by member state (Sources: European Commission, 2020b and 2022c)

Land restoration post mining

In line with the “polluter pays principle”, coal companies have a good record of restoring the landscape at mines and power plants, often leading to a net increase in biodiversity. In some of the EU’s mining regions, dedicated agencies, companies or foundations have been set up to organise mine closures, the rehabilitation of mining sites and the ongoing tasks of subsidence monitoring, water management and gas control, such as SRK in Poland and the RAG Foundation in the German Ruhrgebiet and Saarland. The energy transition away from coal means an acceleration of these efforts, often earlier than planned. This is recognised in the Just Transition Mechanism, as territorial just transition plans must address issues such as land restoration, soil contamination, water treatment, geophysical instability, and other environmental hazards.

Research and innovation can support transition

An important source of funding for the coal sector’s transition is the EU Research Fund for Coal and Steel (RFCS). This fund has the clearly stated goal to support research projects on formerly operating coal mines or coal mines in the process of closure and related infrastructure in line with the EU treaties and the European Green Deal. This includes the methane abatement and use projects that are excluded from the Just Transition Mechanism. In the recently awarded Mine-to-H2 project, partners will demonstrate how existing mine water management installations can be used together with renewable energy sources and an electrolyser to produce green hydrogen. This is just one example of how innovative solutions can repurpose coal-related infrastructure in the regions, create new economic value, and offer continued, high-skilled employment.

A long-term perspective on just transition

If supported with sufficient, well-targeted, long-term funding, the energy transition is an opportunity for the EU to show that structural change does not need to be feared. As other sectors of the economy must also curb their emissions, they will face challenges like the coal sector. The automotive sector of the 2030s will look very different from today as long supply chains must switch to produce components for electric vehicles in an increasingly globalised market. The reverse is also true: if the just transition is seen to be failing, EU policy makers will struggle to convince citizens and stakeholders to support further initiatives under the European Green Deal.

The coal regions will need support beyond 2027; according to the REPowerEU Action Plan, EU coal consumption in 2027 will be at 75% of 2020 levels, i.e. around 340 million tonnes. If the EU wants to continue the path of a gradual coal phase-out, continued support will be needed. At the same time, policy instruments should be flexible enough to support evolving carbon capture and storage technologies, as well as to protect against sudden energy-supply crises, as witnessed in 2021 and 2022. It will take time and effort to replace the energy security that coal offers.

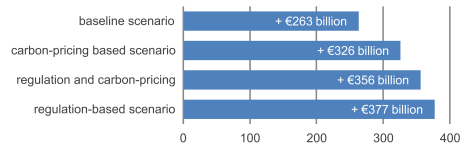

Figure 12 – Additional investment needed for an energy transition in the EU, 2021 to 2030 (Source: European Commission, 2020c, p.69)

Economists and scientists believe the race to net-zero emissions will lead to higher, more sustainable growth. They do not agree, however, on the costs of energy transition. Some compare the challenge to the Arab oil embargo of 1973 and resulting oil price shock which saw prices quadruple in the first quarter of 1974, leading to inflationary pressures and slower growth in all Western economies. For some sectors, the rapid increase in carbon prices in the EU coupled with high fossil gas prices have a similar impact today.

According to the European Commission, additional investments in the EU energy sector in the decade to 2030, compared with the previous decade, should be in the range of €263 billion to €377 billion, or 1.5% to 1.8% of GDP (Figure 12). Although the impact on individual member states is still to be assessed by the European Commission, the additional investment over a business-as-usual scenario is about €2 000 per household – the cost of a room-sized heat pump. While incentives and subsidies could help, it is not clear whether governments are willing or able to increase national debts.

If these green investments replace other, more productive investments, they may have a similarly negative impact on growth as the oil shocks of the 1970s; reducing fossil fuel use does not necessarily increase productivity. More generally, the rapid market changes will mean job losses in some sectors, while others struggle to find the skilled workers they need, thus driving wages and inflation higher as in the 1970s. The challenges of a clean energy transition should not be underestimated!

1 Estimated from Storchmann, 2005; Frondel et al., 2006; European Commission, 2011; and Oei et al., 2020.